We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

Cholesterol: Everything You Need to Know

Table of Contents

- What is Cholesterol?

- Why is Cholesterol Controversial?

- “Good” Cholesterol vs. “bad” Cholesterol

- What are Healthy Cholesterol Levels?

- What Causes High Cholesterol?

- Food Choices and Cholesterol

- How to Optimize your Cholesterol Levels

- Low Carb, High-Fat diet, and Cholesterol

- The Verdict on Cholesterol Levels

Cholesterol: it’s a word that strikes fear into the hearts of health-conscious people everywhere.

This fear, however, isn’t grounded in science. The truth is that cholesterol is found in virtually every cell in your body and essential for every form of animal life.

In this guide, we’ll be looking at what the science says about cholesterol — no medical misinformation or fear-mongering included.

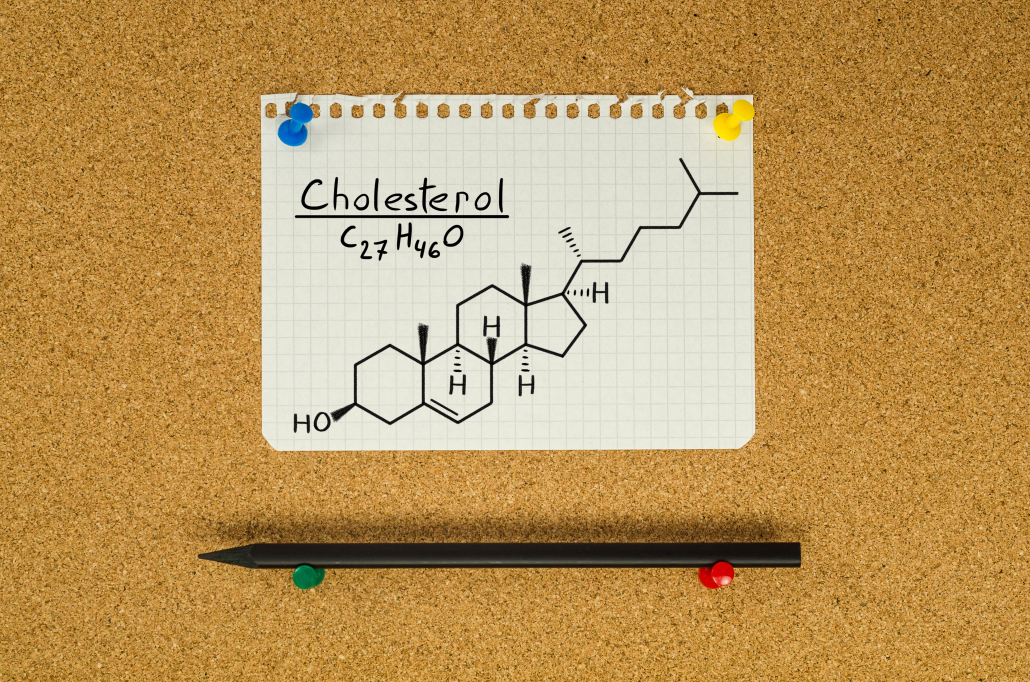

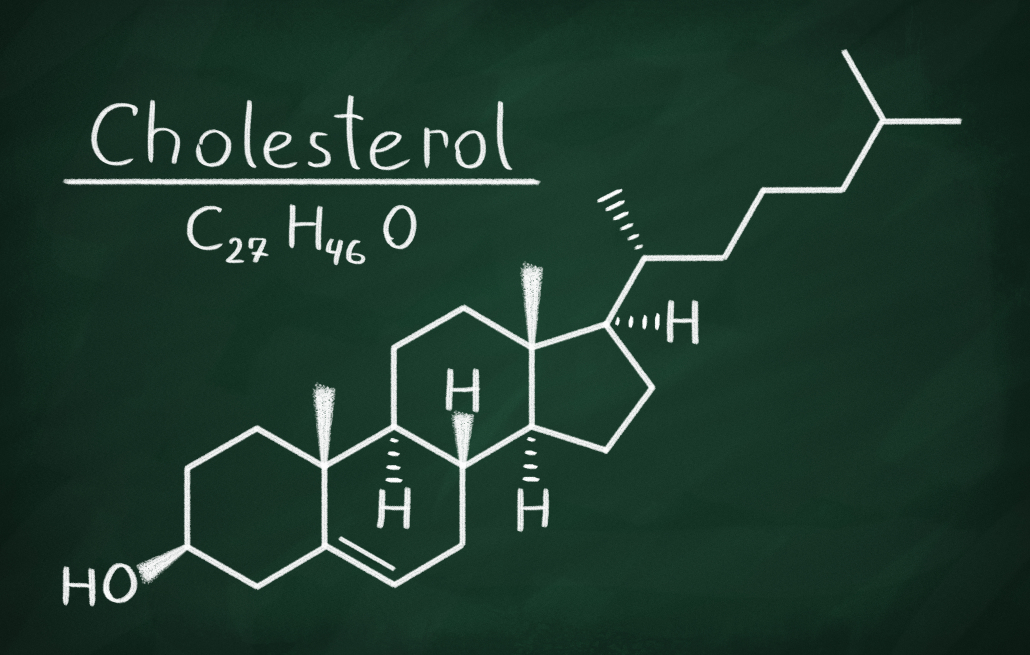

What is Cholesterol?

Cholesterol is a sterol lipid (fat) essential for the life of all animals, including humans. It’s found in virtually every cell of your body and fuels some of the most important physiological functions.

Image from wikipedia.org

Cholesterol fast facts

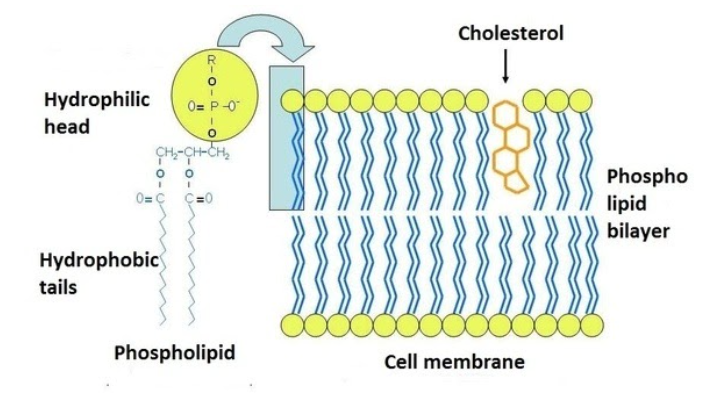

- Cellular integrity | Cholesterol forms part of the phospholipid membrane of nearly all the cells in the body. It is integral to cell structure, fluidity, and permeability.

- Myelin formation | The myelin sheath that ‘cushions’ nerve cells relies on cholesterol for its structure, too.

- Hormone synthesis | Cholesterol is needed to make the hormone pregnenolone, which in turn makes cortisol, testosterone, progesterone, DHEA, estrogen, vitamin D3, and more.

- Creation of bile acids | Cholesterol is converted into bile acids in your liver, which helps you digest dietary fats and absorb fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K2.

Where does cholesterol come from? Only 20% of the cholesterol in your bloodstream comes from dietary cholesterol — i.e. what you eat. Your liver makes the rest.

Image from Quora

Dietary cholesterol 101

Dietary cholesterol is mostly found in animal foods like meat, eggs, shellfish, cheese, and other dairy products. Organ meats are also very rich in cholesterol.

Yet even the richest food sources of cholesterol contain only trace amounts. Cholesterol is measured in milligrams, not grams, and it contains no calories.

| High cholesterol foods | Cholesterol mg per 100 grams |

| Beef brain | 3100 |

| Egg yolk | 1085 |

| Caviar | 588 |

| Fish oil | 521 |

| Foie Gras | 515 |

| Roe | 479 |

| Egg | 373 |

| Lamb kidney | 337 |

| Pork liver | 301 |

| Clarified butter / Ghee | 256 |

| Butter | 215 |

| Lobster | 200 |

| Heavy Whipping Cream | 137 |

A food’s cholesterol and fat content can have unexpected relationships. For example, certain dairy products are high in fat and lower in cholesterol, while many shellfish are high in cholesterol yet low in fat.

The cholesterol found in meat or eggs is mostly in its esterified form, which means it can’t always be used by your body. And in the instances when esterified cholesterol is used, it doesn’t often correlate with increased serum cholesterol levels. That’s because eating more cholesterol triggers your liver to produce less cholesterol, resulting in overall cholesterol homeostasis.

Nonetheless, controversial guidelines to lower cholesterol by simply eating less of it have persisted.

Why is Cholesterol Controversial?

Not many food substances are as misunderstood as cholesterol. This can be attributed to two major factors: faulty initial research, and inaccurate measurement methods.

Faulty Initial Research

The cholesterol controversy began nearly 100 years ago when Russian scientists fed cholesterol to rabbits and found that they developed atherosclerosis–the build-up of plaques along the inner walls of the arteries.

This finding paved the way for mainstream medicine to identify high cholesterol as bad for the heart — but it was premature. Further studies found that rabbits respond to cholesterol differently than many other animals (including humans).

Yet even rabbits don’t develop atherosclerosis if their high-cholesterol diet is supplemented with thyroid hormone, which helps them process it.

By the mid 1930s it was generally accepted that high cholesterol was caused by hypothyroidism, not dietary cholesterol. Physician Broda Barnes had success treating cholesterol problems with thyroid — using little more than a patient’s body temperature as his guide!

Another confounding factor in these early studies is the possibility that the cholesterol they used was oxidized. Studies show that the immune system can mistake oxidized cholesterol for bacteria. The immune system responds by sending inflammatory cells that damage the inside of the arterial wall, and can lead to heart disease.

But dietary cholesterol from healthy whole-animal sources isn’t oxidized. So these early findings may be even less conclusive.

The science connecting hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol) and hypothyroidism was largely forgotten by the time vegetable oil production began ramping up in the 1950s.

Vegetable oil, like many other semi-toxic substances, was shown to correlate with a modest lowering of cholesterol. This ‘finding’ happened to fit perfectly into the emerging medical narrative that low cholesterol was good and high cholesterol was bad.

In other words, consumerism drove science — not the other way around. Eventually a combination of shady marketing and selective science led people to believe the low-cholesterol=good narrative. This narrative is still confusing people today.

Margarine was hailed as a health food when it first came out. Image from Pinterest

Inaccurate Measurement Methods

Even if high serum cholesterol was harmful, the standard method of testing one’s cholesterol levels is prone to error.

“Standard cholesterol testing is largely irrelevant,” says MD Peter Attia. “You should have a lipoprotein analysis using NMR spectroscopy [instead].” Cholesterol’s role within the body is complex enough to warrant equally sophisticated testing methods. Anything short of this method can produce misleading results.

Making matters more complex, your cholesterol levels vary throughout the day depending on energy fluctuations. If you just ate a large, fatty meal, your serum cholesterol will be higher; if you’ve been practicing intermittent fasting, your cholesterol will be lower. So the the time at which you are tested makes a difference.

“Good” Cholesterol vs. “bad” Cholesterol

Not all cholesterol is created equal. Certain types of cholesterol are indeed a cause for concern. Cholesterol can’t move through the bloodstream without assistance from other substances, so it recruits the help of one of two lipoproteins: LDL and HDL.

“Bad” cholesterol: LDL

LDL (low-density lipoprotein) is the type of cholesterol referred to as “bad” cholesterol.

LDL’s primary role is to carry cholesterol and triglycerides to cells. Once delivered, these substances can provide energy and repair cellular damage.

Recent science shows that the most important cholesterol marker is the LDL-p, (LDL particle number). This number describes how many LDL particles are floating around in your bloodstream.

Despite the LDL-p’s importance, most standard blood tests only measure LDL-c, or how much cholesterol your LDL particles are carrying around. Another important metric is the relationship between your LDL-p and LDL-c numbers. If LDL-p is low, then you probably don’t need to worry about your cardiovascular health — even if LDL-c is high.

Just as important as the number of LDL particles in your bloodstream is their function. LDL are prone to shuttling cholesterol to the wrong place, which is when trouble can begin. LDL’s that dump cholesterol into artery walls over long periods of time can cause atherosclerosis, heart disease, and other problems.

To summarize, not even “bad” cholesterol is inherently bad. It usually only becomes a problem when it shuttles cholesterol to the wrong places. Otherwise, even LDL can contribute to the steroid synthesis and cellular structuring we mentioned earlier.

“Good” cholesterol: HDL

HDL (high-density lipoprotein) is the type of cholesterol referred to as “good” cholesterol.

HDL, however, isn’t actually cholesterol at all. It’s a lipid-carrying protein that transports cholesterol throughout the body. Compared to LDL, HDL seems to do a better job of shuttling cholesterol around.

HDL’s primary role is collecting excess cholesterol and transporting it to the liver, where it can be recycled or destroyed. This prevents the accumulation of cholesterol in the blood, which keeps cholesterol from building up in blood vessels and causing heart disease. Researchers call this process “cholesterol efflux.”

HDL particles also have anti-inflammatory and anti-clotting properties. The combination of these beneficial properties is why HDL is associated with cardiovascular health. HDL can protect against LDL — but, more than that, it protects against actual cardiovascular problems.

What are Healthy Cholesterol Levels?

Unfortunately, the faulty initial research and inaccurate measurement methods mentioned earlier have gone a long way towards shaping the cholesterol guidelines still in use today.

Before getting into these guidelines, let’s take a quick look at how cholesterol levels are quantified.

We measure cholesterol in denominations of milligrams per deciliter (1/10th of a liter) of blood. This metric is designated by mg/dL. To determine a person’s total cholesterol number, their HDL and LDL levels are added together.

So, what are considered healthy cholesterol levels?

Though controversial, blood cholesterol levels between 200 and 240 mg/dL have historically been considered ‘normal.’

But in older people, cholesterol levels much higher than this have been associated with longevity!

A 1989 study of elderly women found that those with levels over 270 mg/dL had the lowest mortality rates. Even roundworms live longer when they have their genes edited to produce more cholesterol.

While gene-editing methods are obviously unproven, this finding further supports cholesterol’s protective, anti-stress effect. Optimizing cholesterol levels may allow the body to make the right levels of hormones, like cortisol and cortisone, that facilitate a healthy stress response.

Despite these historic and scientific precedents, most mainstream sources today consider a total cholesterol level of under 200 ideal.

Breaking Down Cholesterol Recommendations

In order to stay under 200 mg/dL total, LDL (“bad” cholesterol) should be less than 110 mg/dL and HDL (“good” cholesterol) should be under 90.

With HDL, however, it’s important not to go too low. Your HDL should be at least 35 mg/dL — preferably higher. The more HDL you have, the better your protection against heart disease. Cardiologist John Higgins says that “the sweet spot” for HDL “is between 60 and 80 mg/dL.”

Other mainstream recommendations include:

- Lowering LDL cholesterol to under 190 mg/dL

- Raising HDL cholesterol to ~ 60 mg/dL

- Lowering total cholesterol to under 200 mg/dL

- Lowering triglycerides to under 150 mg/dL

What Causes High Cholesterol?

Some of the risk factors for high LDL (“bad” cholesterol) include:

- Hypothyroidism

- Poor food choices

- Inactivity

- Smoking

Hypothyroidism

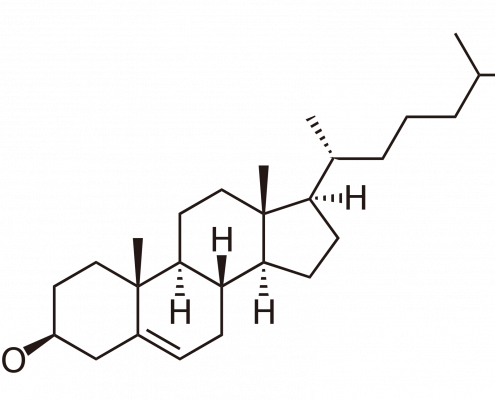

In order to understand why thyroid health can impact cholesterol levels, it’s important to understand what dietary cholesterol actually becomes when it enters your body.

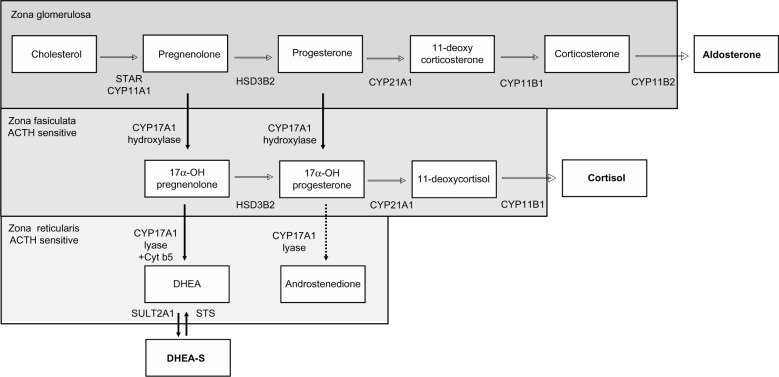

Earlier we mentioned that cholesterol is the precursor, or building block, for the “steroid hormones”: pregnenolone, testosterone, progesterone, DHEA, and estrogen.

The many hormones made from cholesterol. Image from ResearchGate

These conversions take place thanks to a person’s thyroid hormone, which converts cholesterol into other types of hormones in different areas of the body. Slow thyroid activity means steroid hormones don’t get produced quickly enough which can lead to a virtual backlog of cholesterol.

Food Choices and Cholesterol

Since the famous (or infamous) 1958 Seven Countries study by Ansel Keys, various dietary recommendations have been made to try to improve cholesterol levels. Keys’s observational study found a correlation (but not causation) between saturated fat intake and heart diseases.

Over the preceding decades, researchers have developed a more sophisticated understanding of cholesterol and devised better studies to test for the relationship between diet and cholesterol.

The link between diet and cholesterol, and how it affects our health is still a hotly debated topic within mainstream nutrition-science establishments. The two dietary factors most scrutinized are saturated fat and sugar.

Saturated Fat and Cholesterol

For decades saturated fat has been demonized because some studies demonstrated a causal link between saturated fat and moderate increases in LDL cholesterol. These findings are often coupled with other studies showing a causal link between LDL cholesterol and coronary heart disease.

However, there are no studies showing convincing evidence for a direct link between saturated fat and heart disease.

More recent and higher quality research reveals that the effects of saturated fat on heart disease are far more complicated and nuanced.

This outlook is highlighted by recent analysis of numerous studies leading to a shift in mainstream perceptions of saturated fat. A 2019 report by 19 leading researchers concluded that the scientific evidence does not support WHO guidelines for reducing dietary saturated fat.

The report states that these guidelines can weaken the effect of the overall guidelines on chronic disease incidence and mortality. Similar findings are voiced in a 2020 analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

These studies reveal that factors including food sources of saturated fat (are you getting it from a steak or a cookie loaded with sugar?), individual responses to saturated fat intake, and overall diet changes in relation to increases in saturated fat intake need to be taken into account.

Sugar and Cholesterol

The average American eats the equivalent of about 26 teaspoons of added sugar a day. That’s nearly 3 times more than recent heart disease prevention guidelines.

And this is without including the carbohydrates (which all break down to simple sugars that raise blood sugar), that we get from fruits, grains, and all other vegetables.

For a long time, researchers have known that excess carbohydrates contributes to obesity, diabetes, and other conditions linked to heart disease. And recent research links excess carbs to unhealthy cholesterol and triglyceride levels and increased cardiovascular mortality.

In the study, people who consumed the most added sugar had the lowest HDL, or good cholesterol, the highest blood triglyceride levels, and were most likely to die from cardiovascular disease.

Participants who ate the least sugar had the highest HDL, and the lowest triglyceride levels.

Another 2010 study analyzed 6,113 adults who participated in the large, ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The study showed that the more sugar participants ate, the lower their HDL and higher their triglycerides. And compared to people who ate the least sugar, people who ate the most sugar were three times more likely to have low HDL levels.

The study authors link the added sugar to an increase in processed foods, which are also high in another food that has negative effects on cholesterol levels–trans-fats.

Indeed, trans fats raise LDL far more than saturated fats do. Highly polyunsaturated fats (contained in many vegetable oils) may also contribute to high cholesterol more than originally thought, since their cholesterol content easily oxidizes to form harmful byproducts.

Inactivity

Chronic sitting and lack of movement can also have negative effects on your cholesterol levels. Even a few days of inactivity can result in higher LDL.

Thankfully, exercise can help. One study found that athletes have higher HDL cholesterol (“good” cholesterol) than their inactive counterparts. That’s just one more reason to pick up walking if you haven’t already. And if you’re looking for more low-impact intentional movement, yoga is a great practice to explore.

Smoking

The carcinogenic chemicals in smoke can make your blood thicker and less supple over time. Smoking can also raise your blood pressure and damage the delicate linings of your arteries.

All this damage makes it harder for cholesterol to be transported to the right places. Perhaps unsurprisingly, smoking lowers HDL cholesterol and raises your LDL cholesterol. This effect is most pronounced in women.

Can High Cholesterol be Beneficial?

Cholesterol is found in so many nourishing foods, produced naturally in large quantities by our bodies, processed into critical hormones by our thyroid glands, and strongly correlated with improved mental health and longevity.

This begs the question: Could high serum cholesterol levels be protective, and could they be one of the body’s tools it uses to protect against harm?

Some experts think so. And there’s a growing body of research investigating this question. One study of healthy young women found that those with low cholesterol were more likely to be depressed and anxious. The study’s researchers theorized that correspondingly low levels of vitamin D, the “sunshine hormone,” might be responsible.

Cholesterol may improve other facets of mental health, too. The Framingham heart study looking at 1948 people found that people with cholesterol levels in the ‘ideal’ sub-200 range have slightly lower “verbal fluency, attention/concentration, abstract reasoning, and a composite score measuring multiple cognitive domains” than those with ‘high’ cholesterol.

Other studies highlight a link between cholesterol and cognitive function, showing that cholesterol may promote neural growth and plasticity.

These findings bring us to a surprising possibility: far from being the cause of health problems, high cholesterol levels may be a protective, symptomatic response to issues like hypothyroidism and obesity.

How to Optimize your Cholesterol Levels

Getting your cholesterol levels back into the ideal 200-270 mg/dL range is often quite simple, regardless of whether they’re currently too high or too low. We’ll focus on four of the most elemental ways you can optimize your cholesterol:

- Thyroid health

- Weight loss

- Exercise

- Healthy fats

Thyroid health

This method is important, but implementing it can be challenging because medical guidance is usually required. If you exhibit the hallmark signs of hypothyroidism — including low body temperature, cold extremities, water retention, weight gain, high cholesterol, and even arthritis–you may want to ask your doctor to get check your thyroid.

The possibility of subclinical hypothyroidism shouldn’t be neglected, either. To promote thyroid health, consider eating iodine (seafood and salt are two great sources) and avoiding processed polyunsaturated fats.

Weight loss

A study done by the American Diabetes Association found that weight loss has several beneficial effects on cholesterol. Weight loss may increase the breakdown of bad cholesterol and have a sparing effect on good cholesterol, resulting in a much better lipid profile.

Another study found that the reduced blood pressure and reduced cholesterol levels seen in weight loss were closely related. The patients in this study lowered their cholesterol by up to 45 mg/dL as they lost weight and improved their health.

Exercise

Getting half an hour of physical activity per day can boost your HDL cholesterol and lower your LDL cholesterol. Some studies have shown that exercise’s beneficial impact on cholesterol levels grows more and more apparent with age, since exercise lowers cholesterol more in those above the age of 60.

Gentle exercises like yoga and pilates may be best since they provide cholesterol-lowering capabilities in a stress-free format. Walking, bicycling, and tennis are also good — as long as you enjoy them!

| Inactive | Active |

| HDL at baseline | HDL up 20% |

| LDL at baseline | LDL down 15% |

Eating Healthy Fats

When the average person thinks of heart-healthy dietary fats, they might see an image of vegetable oils high in polyunsaturated fats. But unfortunately, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Saturated fat appears to be more protective against heart disease than unsaturated fat, in spite of its potential effects on cholesterol levels. In 2014, the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study found an inverse relationship between saturated fat intake and cardiovascular problems.

Leading nutritional researcher Mary Enig, affirms that avoiding saturated fat may only make things worse. “If you are avoiding foods containing saturated fat and cholesterol, you will not only deprive your body of vital nutrients, but the foods that you consume as substitutes will contain many components—polyunsaturated oils, trans fatty acids, refined sugar—that have been associated with increased rates of heart disease,” she explains.

This concept leads us to what might be the best way to optimize cholesterol of all: a high fat, low-carb keto diet.

Low Carb, High-Fat diet, and Cholesterol

Eating a low-carb, high-fat diet almost always means eating high cholesterol foods like eggs, bacon (or better yet, fresh pork belly), full-fat dairy, and organ meats.

Although it may sound like common sense that eating a high-fat low-carb diet filled with cholesterol-rich foods would raise blood cholesterol levels, that’s not the way it actually works.

As we’ve discussed earlier, the body does a good job of regulating your blood cholesterol by controlling how much cholesterol it makes.

When you eat more cholesterol, your body makes less, and vice versa. Because of this regulating ability, studies show that foods high in dietary cholesterol have very little impact on blood cholesterol levels in most people.

For most people on high-fat low-carb diets, there is a slight increase in overall cholesterol due to an increase in heart-healthy HDL. Bad LDL particle concentrations decrease (LDL-P). And the size of LDL cholesterol particles increases–all positive markers for cardiovascular health.

At the same time, dangerous VLDL cholesterol concentrations in the blood generally decrease as well. Weighing the evidence, for most people the benefits of HFLC diets on cholesterol levels outweigh the negatives

The Verdict on Cholesterol Levels

Cholesterol is an essential substance that sustains life in all animals including humans.

When considering the evidence, it becomes clear that cholesterol is not the public enemy that the medical profession once thought it was.

Dietary cholesterol has little to no effect on blood cholesterol levels. In addition, high cholesterol levels may well be a downstream symptom of other chronic health issues including hypothyroidism, hormonal imbalances, obesity, and more.

On the other hand, more recent research has discovered a causal link between dietary carbohydrates and unhealthy cholesterol levels in humans.

A diet rich in whole foods that are naturally high in cholesterol and low in added sugars and other carbohydrates is likely protective against health problems associated with unhealthy cholesterol levels.