We include products in articles we think are useful for our readers. If you buy products or services through links on our website, we may earn a small commission.

Why Eating Meat is Good for The Environment: Follow the Science

In this article, we’ll look at the science-backed links between eating meat and the environment and show how eating meat can be good for the environment.

Even people who love meat and eat meat for its many health benefits have concerns about the environmental impact of eating meat.

The dominant narrative is that meat is bad for the environment, and therefore we should limit our meat consumption. But, as we will see, eliminating meat is not the solution.

Livestock animals are integral to a sustainable and healthy food system. In fact, cows can be a part of the solution to rampant soil degradation and climate change.

Let’s explore the narrative that meat is bad for the environment, add in the missing pieces, and show how animals are key to sustainable ecology.

We’ll start by looking at each of the subject related to meat and the environment, beginning with water.

Table of Contents

Cows Use too Much Water

Much has been made about the use of water in raising livestock, especially cows.

For example, according to the World Economic Forum bovine meat requires over 15,000 liters of water to produce 1kg of food, much more than fruits and vegetables.

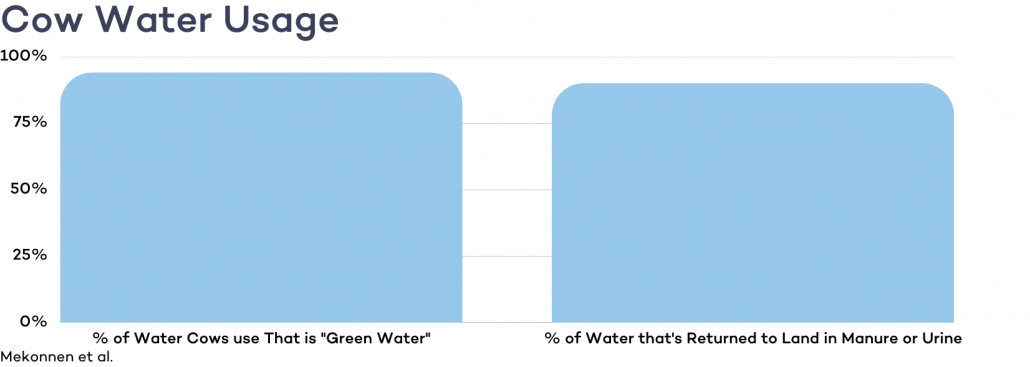

However, omitted from this conversation is the fact that 94% of the water that cows use is rainwater, or “green water.” This water would be available to cows whether they were there or not.

Furthermore, 90% of the water the cows consume is returned to the land through urine and manure, both of which are powerful natural fertilizers that maintain soil integrity and fertility.

Cows do use a lot of water, but leaving out the fact that cows enhance the soil through their use of mostly “green water” is bad science and false reporting.

Another line of reasoning that brings water use into the argument against cows is that lots of water goes into growing the feed for cows.

When it comes to pasture-raised grass-fed cattle, this is simply not the case. They graze on grassy fields fed by rainwater.

But even if we consider conventional feed-lot cattle who get their feed from agricultural products, much of the food they eat are byproducts (ie. corn stock) of human food production and would end up as waste products.

Similarly, even conventional “feed-lot” cattle spend 1/2-1/3 of their life grazing in open pasture.

Cows Take Food that Humans Humans Need to Eat

The global population is exploding. At the same time, access to food is becoming more insecure as climate change disrupts once fertile regions.

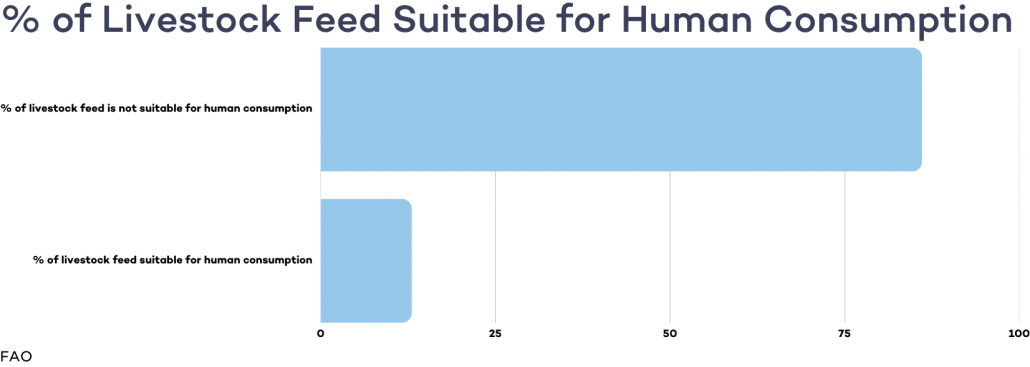

But according to a bellwether study by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), livestock is not to blame.

Anne Mottet, a researcher and Livestock Development Office at the FAO states, “I came to realize that people are continually exposed to incorrect information about livestock and the environment that is repeated without being challenged, in particular about livestock feed.”

The FAO study determined that 86% of livestock feed is not suitable for human consumption.

If livestock didn’t consume these plant byproducts, mostly from grains and seed (vegetable) oils used in processed foods, they would become an environmental burden, fermenting in landfills and producing even more greenhouse gasses.

Examples of food waste used to feed American cattle include citrus pulp and cranberry mash from making juice, corn stocks, and brewers’ grain from beer production.

It is also true that livestock animals consume food that could be eaten by humans. But not nearly as much as previous estimates. The FAO study highlight overlooked aspects of meat production, including:

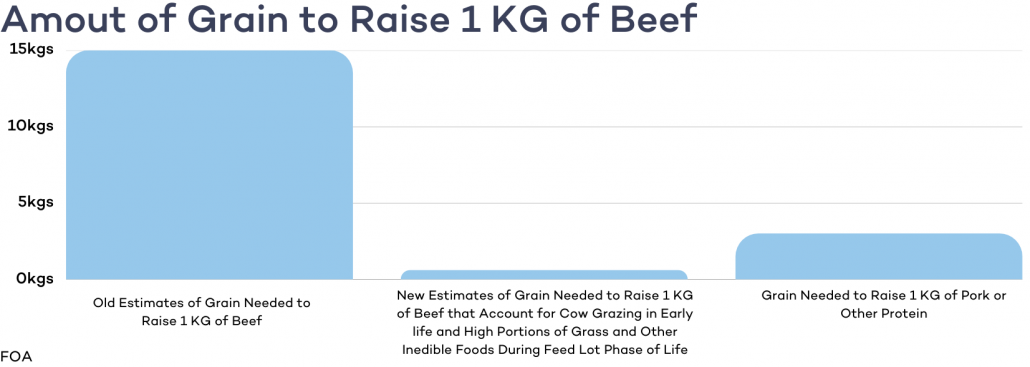

- Previous studies overestimated the amount of grain needed to raise 1 kg of beef as between 6-20 kg

- An average of only 3 kg of cereals are needed to produce 1 kg of any kind of meat, including pork–which can only be raised with feed and cannot rely on grazing

- Because cows graze and forage, cattle only needs 0.6 kg of protein from edible feed to produce 1 kg of protein in milk and meat

To be fair, grains fit for human consumption account for 13% of livestock dry feed.

However, dairy products and meat are much more nutrient-dense and healthier than grains while providing more protein output than input.

Grains are also high in plant toxins and antinutrients like phytic acid, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies and phytohormones which can negatively impact fertility.

Ruminant animals like cows and sheep have the ability to break down plant toxins while metabolizing plant fibers into beneficial fatty acids that we consume in meat and dairy.

certain production systems contribute directly to global food security, as they produce more highly valuable nutrients for humans, such as proteins, than they consume.

Meat is only a Luxury Produced and Consumed by the Global Rich

One billion poor people, mostly pastoralists in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, depend on livestock for food and livelihood.

Globally, livestock provides 25 percent of protein intake and 15 percent of dietary energy.

Livestock contributes up to 40 percent of agricultural gross domestic product across a significant portion of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa but receives just three percent of global agricultural development funding.

Meat Takes Land that Could be Used for Farming

The idea that cows take up land that could be used for farming is also not accurate. Most of the land that cows roam on is too hilly or rocky for plant agriculture.

The Department of Agriculture estimates that 60-70 of the agricultural land is best suited to grazing.

The majority of the caloric energy in plants that live on this land is contained in cellulose, which is indigestible for humans and many most mammals. But cattle, bison, sheep and other ruminant animals digest cellulose, making these vast stores of solar energy available to humans.

When the data is crunched to show that turning livestock pasture into plant foods increases caloric yield, plant-based proponents are referring to mono-crop industrial agriculture yielding mostly grains and vegetable oils–the inflammatory foods that are likely responsible for our epidemic of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. .

Furthermore, if we’re just considering Western nations like America with soaring obesity rates, producing more calories is not a concern. What we need is more nutrient-dense, lower-carb, and more satiating foods. In a word, meat.

Cows Cause Biogenic Methane vs. Fossil Fuel Emissions

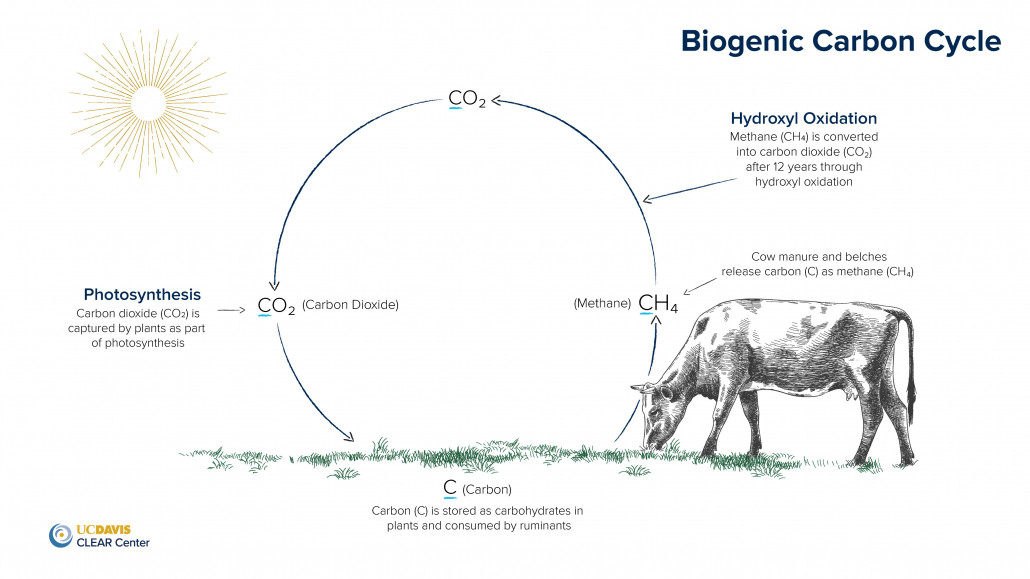

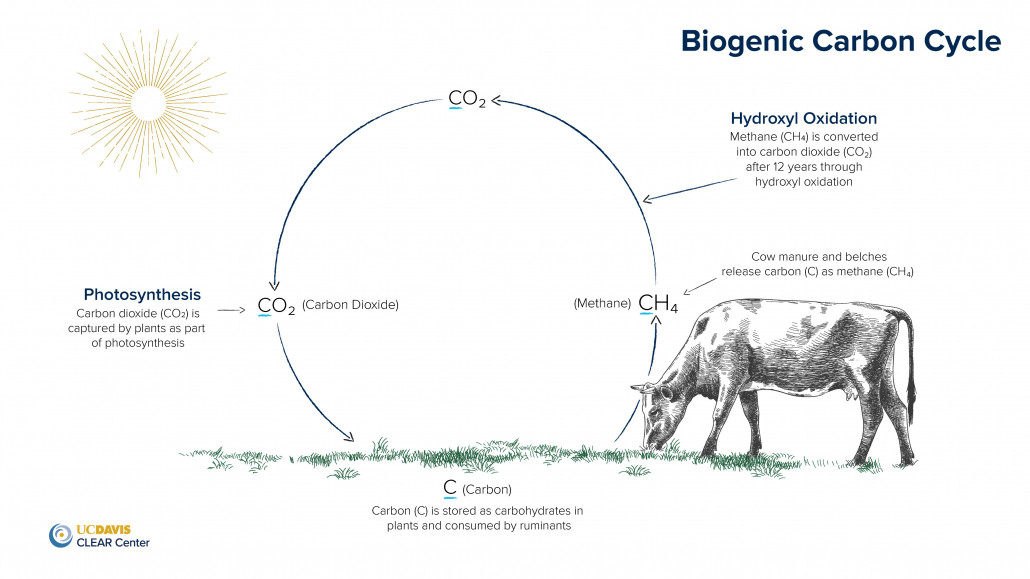

Cows produce and belch methane in the process of fermenting cellulose from plants into fatty acids. Methane is a greenhouse gas like the carbon dioxide emitted from cars and industry.

Anti-meat proponents like to point out that per gram, methane has about 21 times the greenhouse potential of carbon dioxide. But unlike carbon dioxide, biogenic methane breaks down fairly quickly in the atmosphere.

As U.C. Davis researcher Frank Mitloehner explains, methane from cows is part of a natural carbon cycle that should be analyzed differently than the greenhouse gases unlocked from the earth and emitted into the atmosphere through burning fuel.

Cows eat grass, an existing form of carbon. Bacteria in the cows’ stomach ferments the grass. Methane is burped out as a byproduct of this digestive process.

After 10 years, methane breaks back down into water and carbon dioxide that gets cycled back into the ground via photosynthesis. The cycle repeats again and again.

Even though methane from fossil fuels and living organisms like cows are chemically identical, they have a different warming impact.

Cows use molecules that are already in the atmosphere and cycle them back and forth.

Fossil fuel carbon is new carbon emitted into the environment and is not part of a natural carbon cycle.

A joint FAO/IAEA report revealed that until 2003 it was incorrectly believed that methane levels correlated with increasing amounts of livestock. The report found that there was no relationship between increasing ruminant numbers and changing atmospheric methane concentrations.

A 2018 report from NASA showed that atmospheric methane has risen sharply since 2006, and attributed the increase to emissions from oil and gas production and microbial production in rice paddies and marshes, not from livestock.

In addition to understanding livestock methane as part of a natural carbon cycle, there are also effective measures being taken to reduce livestock methane.

For example, California is a world leader in working with dairy farmers to capture methane emissions from manure and turn them into renewable natural gas using anaerobic digesters.

Methane capturing technology has reduced California’s livestock methane emissions by 25% since 2013, and the state is on track to meet its goal of reducing livestock emissions by 40% by 2030.

C02

In addition to methane, the Co2 emissions incurred by dairy and beef production have fueled the narrative that cows are bad for the environment. However, this narrative is supported by faulty science.

In 2006 the Food and Agriculture Organization released a paper titled Livestock’s Long Shadow. The report stated that livestock produced 14.5% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, which was more than produced by transportation.

But this was a major misrepresentation. For cattle, they accounted for emissions from every aspect of the life cycle, but for cars, they only counted what came out of the tailpipe while driving.

The authors did not account for emissions produced by the factories building the cars, all the energy-intensive and highly polluting production processes that go into extracting and refining raw materials into useable parts, or the building and maintaining of roads.

Though other researchers quickly pointed out that the comparison was misleading and the report was updated by its authors, the talking point had been repeated so many times that it is still lodged in the anti-meat narrative.

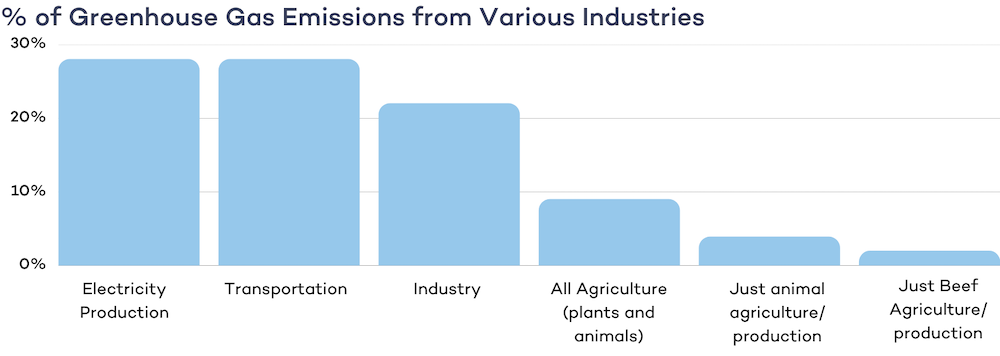

The true story about greenhouse gas emissions and meat production looks like this :

- 28% of greenhouse gas emissions are from the production of electricity

- 28% of are from transportation

- 22% are from industry

- 9% are from all agriculture, including plant and animal production

- 3.9% of total us greenhouse gas emissions come from animal agriculture

- 2% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come beef production

Is that 2% really worth eliminating? Especially when considering that beef is among the healthiest and most nutrient-dense foods on earth.

That 2% has to be replaced with something–and that something would inevitably be less nutritious.

The story gets even more complicated when considering a recent study from Carnegie Mellon University found that if Americans were to follow the mainstream dietary recommendations for a ‘healthy’ mix of more fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and seafood:

- energy use would go up by 38%

- water use by 10%

- greenhouse gas emissions by 6%

In light of these findings, that 2% is doing a lot of work in terms of supporting the environment and limiting further resource exploitation and greenhouse gas emissions.

Of course, relying on factory-farmed animals isn’t the answer, but it’s also not the most environmentally problematic aspect of our society or even of our food systems.

For instance, on a per calorie basis, lettuce produces 300% more greenhouse gas emissions than conventional bacon.

Regenerative Agriculture

The relationship between meat production with water and land use, and greenhouse gas emissions has almost exclusively been considered in the context of industrial farming practices.

But meat isn’t just “not that bad for the environment” or “better than mono-crop agriculture,” as the analysis above suggests.

If raised with regenerative agriculture practices, eating meat is downright good for the environment.

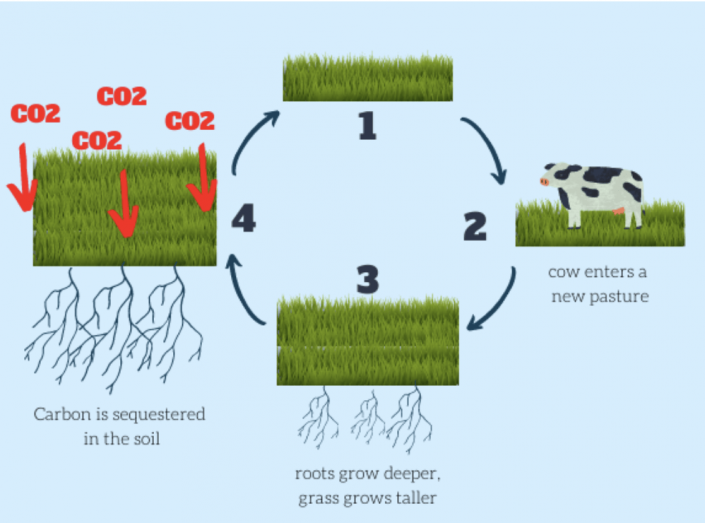

“Regenerative agriculture” or “carbon farming” is a way of raising livestock that sequesters carbon while maximizing soil health.

It works by using a method of rotational grazing that recreates the natural ways that bison roamed American prairies for millennia.

The animals trample their manure into the earth, feeding the soil with beneficial microbes and bacteria and fertilizing the plants that the animals will eat.

Raising Meat for Soil Health

Using livestock to revitalize soil becomes even more important when considering our current and projected states of soil degradation.

⅓ or agricultural land has been degraded. If we continue abusing the soil at current rates the world’s arable topsoil will be totally depleted in 60 years.

Purchasing and consuming meat from the many regenerative “carbon sink” farms like White Oak Pastures in Georgia is a proactive way to support nature’s food chain and sequester carbon.

It’s not a cheap solution, but if you truly care about the environment and honestly pay attention to the science of food systems, it’s the right way.

For the soil to be healthy, it needs animal inputs of manure and urine. Cows are incredible urine and manure machines.

In addition to supporting the soil microbiome, cows increase the capacity of soil to hold moisture, nourishing grasslands with microbial diversity.

Much of the American landscape evolved through this symbiotic relationship between ruminant animals (Bison) and the soil.

Animal vs. Chemical Fertilizers

Any and all soil needs nutrients to grow, and those nutrients have to come from either natural animal inputs or from chemical fertilizers, most of which are products of the petroleum industry.

Animal inputs are much more sustainable and less damaging to the environment.

One of the biggest problems with chemical fertilizers is that they produce runoff that pollutes our oceans and waterways.

In 2008 scientists identified over 400 hypoxic dead zones. These are bodies of water that have been thoroughly polluted by agricultural runoff and industrial waste.

The biggest culprits are fertilizers like nitrogen and phosphorus. The presence of the chemicals produces algae blooms that deplete underwater oxygen levels to the point where that area of water can no longer support marine life.

Where the Mississippi river meets the gulf of Mexico, there is an 8500 square mile dead zone that has decimated the shrimp industry and depleted fish counts. There are other dead zones at the mouths of fertilizer polluted rivers in Oregon and Virginia.

Secondary Environmental Costs

To have an honest and complete discussion about meat and the environment, you need to include secondary environmental costs.

For example, a study of 60,000 households in Japan found that those with the highest carbon footprints ate more fish, vegetables, alcohol, sugary foods, and ate out more often.

The impact of eating meat was shown to pale in comparison to eating out and eating junk food.

The study author commented, “If we think of a carbon tax, it might be wiser to target sweets and alcohol if we want a progressive system.”

Perhaps the biggest secondary environmental costs related to meat consumption have to do with healthcare for preventable diseases.

Eating meat is beneficial for metabolic, digestive, endocrine, heart, and mental health. Low-carb high-fat high-meat diets like keto and carnivore have been clinically shown to improve markers of health in each of these areas.

As the pioneering researcher and dentist, Weston A. Price revealed nearly a century ago, populations who ate traditional diets high in meats and without processed foods were virtually free of the chronic inflammation related diseases that now kill 3 out of 5 people globally.

These diseases, including stroke, respiratory diseases, heart disorders, cancer, obesity, and diabetes are often referred to as diseases of civilization. They stem in large part from our modern diets high in processed grains, seed oils, and added sugars.

Treating these metabolic diseases incurs a huge environmental cost. In 2007 the total effects of health care activities contributed 8% of total US greenhouse gas emissions. That’s 400% more than the U.S. beef industry.

Vegetarian Myth

To sum up the discussion on why eating meat is good for the environment, here’s an excerpt from the Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability by Lierre Keith:

So here is an agriculture without animals, the plant-based diet that is supposed to be so life-affirming and ethically righteous. First, take a piece of land from somebody else, because the history of agriculture is the history of imperialism. Next, bulldoze or burn all the life off it: the trees, the grasses, the wetlands. That includes all creatures great and small: the bison, the grey wolves, the black terns. A tiny handful of species—mice, locusts—will manage, but the other animals have to go.

Now plant your annual monocrops. Your grains and beans will do okay at first, living off the organic matter created by the now-dead forest or prairie. But like any starving beast, the soil will eat its reserves, until there’s nothing—no organic matter, no biological activity—left.

As your yields—your food supply—begin to dwindle, you’ve got two options. Take over another piece of land and start again, or apply some fertilizer. Since the books, pleading and polemical, say that animal products are inherently oppressive and unsustainable, you can’t use manure, bone meal, or blood meal. So you supply nitrogen from fossil fuel.

Do I need to add that you can’t produce this yourself, that its production is an ecological nightmare, and that one day the oil and gas will run out?

Your phosphorous will have to be made from rocks. There’s a reason for the popular image that equates hard labor in prison with chopping rocks. How will you mine it, grind it, or transport it without fossil fuel, using only human musculature and without using slavery?

For your potassium, you’ll collect wood ashes, try some cover crops, and hope for the best. Meanwhile, the soil is turning to dust, clogging the rivers, blowing across the continent. In 1934, the entire eastern seaboard was covered in a thick haze of brown, the topsoil of Oklahoma plowed to cotton and wheat, drifting like an angry ghost to cover the eastern cities and further, to ships hundreds of miles out to sea, a final, fitting tribute to the extractive economies of the civilized.

This is where agriculture ends: in death. The trees, the grasses, the birds and the beasts are gone, and the topsoil with them. More of the same is no solution (p. 44).

Why Eating Meat is Good for the Environment: The Takeaway

When we give an honest reading of the available evidence having to do with meat and the environment, a complex story emerges.

Yes, producing meat, especially conventionally, requires resources of water, land, and petroleum. Yes, cows emit greenhouse gasses.

But these resources and emissions must be considered within a broader accounting that looks at meat production in the context of the total environmental impact of modern life. In this light, meat production, especially from cows, accounts for a small fraction of emissions and returns an abundance of nutrient-rich foods that plant foods simply cannot match or compensate for.

When we look strictly at agriculture, we see that cows belong in our food systems and on our land. The earth needs ruminants to build and maintain topsoil.

Food is complicated: fruits and veggies have the largest water and energy footprint per calorie. Meat, dairy, and seafood have the highest greenhouse gas emissions per calorie.

But there is a way out of this quagmire if you have the means to take it.

Though more expensive than conventional meat, if you want to eat meat in a way that is most beneficial to the environment, regenerative farmed meat is the answer.